For those who were unable to attend, we compiled the key takeaways of the webinar featuring professor Yakov Amihud from the Stern School of Business, New York University.

Professor Amihud’s research revisits his 2002 paper “Illiquidity and stock returns: cross-section and time-series effect”, presenting a return factor of illiquid-minus-liquid stocks (IML) and providing a time series of the illiquidity premium. In his original paper, Amihud concludes that, over time, expected market illiquidity has a positive effect on stock excess returns, which in turn represents an illiquidity premium. In his new research, he found that the risk-adjusted expected return on IML is positive and significant. Particularly, the relation between illiquidity shocks and stock returns was more negative for illiquid stocks in the period after the 2002 paper.

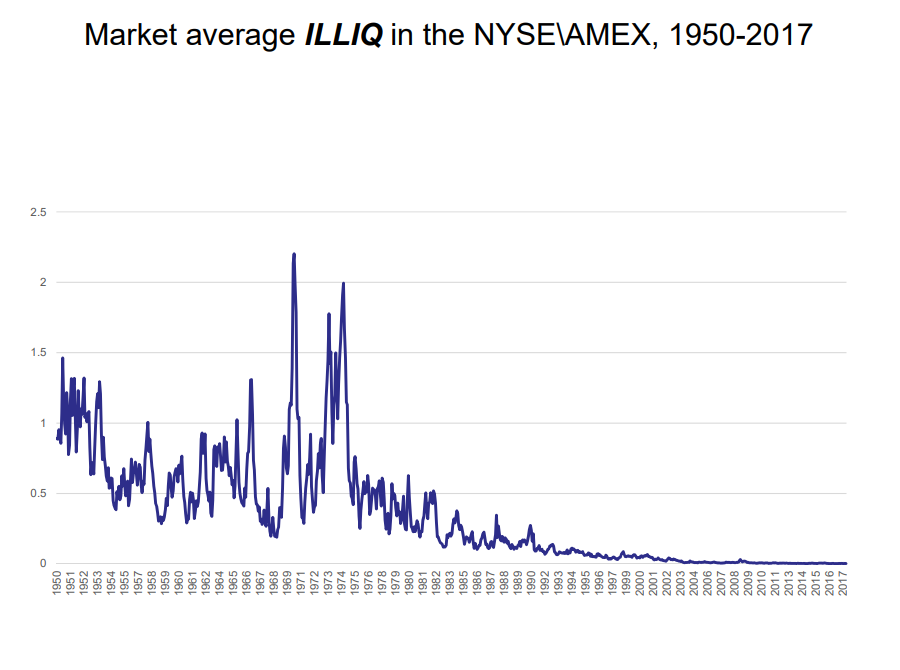

The presentation started with an introduction of the concept of illiquidity, before discussing the effects and determinants of liquidity, such as asymmetric information between informed and uninformed traders, float and trading procedures and mechanisms. Subsequently, Amihud introduced his illiquidity measure (ILLIQ) and showed how illiquidity has changed since the 1950’s: “Illiquidity was high in the 1970’s, but then it started to go down – because the market moved to automation. You immediately see the results: illiquidity is so much lower than it used to be. People sometimes ask me: ‘Why is the market so much higher today than it was in the past? Risk has not changed!’ My answer is: one of the reasons is that the market now is far more liquid than it has been in the past.”

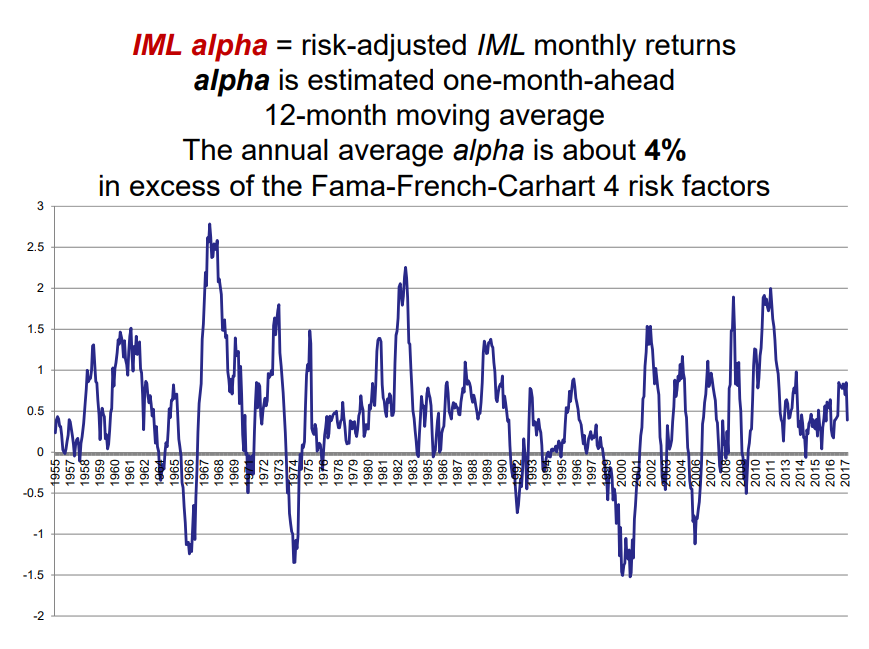

In his research, professor Amihud measured the effect of illiquidity on stock expected returns between 1955 and 2017, which he did by calculating illiquid-minus-liquid (IML) stock portfolio return (a portfolio consisting of 20% most illiquid stocks – the 20% most liquid stocks); this resulted in an alpha of about 4%. Amihud: “When you look at the bigger picture, you see that the risk-adjusted IML stock returns were high in the 1970’s and 1980’s, and that the market took a nosedive around the time of the dot-com bubble, as there was a crash in the market and the internet companies were illiquid. Now, you can see it is flat, about half a percent per year.”

Furthermore, the research found that stock prices fall if there is a significant increase in illiquidity, and that illiquidity is likely to remain higher for an extended period of time. Professor Amihud elaborated on what happens to stock returns in times of unexpected market illiquidity, which he refers to as an illiquidity shock. “When the market becomes illiquid, the price of illiquid stocks falls more than that of liquid stocks. The same can be said for bonds – the price of junk bonds (illiquid) falls relative to investment grade bonds (liquid) when illiquidity rises,” Amihud explains. “When you buy an illiquid stock or bond, you hope to get a higher expected return. However, you should be aware that when the market becomes illiquid and you want to sell the asset, you are in trouble. You should diversify, not only in terms of risk, but also in terms of liquidity. Ultimately, you want to be able to ride the crisis. If the market becomes illiquid and you need to sell to redeem securities, do it with the liquid ones.”

Before concluding the presentation, Amihud touched on the phenomenon of ‘flight to liquidity’, in which bond investors sell their illiquid ‘junk’ bonds and buy liquid investment-grade bonds instead: “My research found that the illiquidity pricing varies by the state of the market. In good markets, investors hardly care about illiquidity. In times of financial distress, bond prices strongly react to liquidity shocks. We refer to this as a ‘flight to liquidity’, which is different than a ‘flight to safety’, from junk bonds to investment-grade bonds.”

Interested in learning more about the research?

Watch a replay of the webinar here: https://vimeo.com/605415203