Inflation is among the most important risks that investors face and the current inflationary period is a very good reminder of that. However, we know fairly little about how individual investors’ respond to inflation, and theory provides conflicting hypotheses on this question. Felix von Meyerinck presented his research ‘Inflation and Individual Investors’ Behavior: Evidence from the German Hyperinflation’ during the Inquire Europe spring seminar on 27 March. (The paper was recently accepted for publication by the Review of Financial Studies.)

For those of you who were unable to attend the seminar, we have created a synopsis of the presentation:

“There are two diverging hypotheses regarding investment behavior during inflationary times. The hedging hypothesis states that investors tend to buy more stocks when inflation rises because they understand that dividends rise with inflation. In contrast, the money illusion hypothesis predicts that investors sell stocks when inflation rises because they confuse nominal and real terms. Specifically, they discount real cash flows with nominal rates, overvaluing stocks at times of high inflation.

In the paper, we introduce a unique dataset containing local inflation and the security portfolios of over 2,000 clients of a German bank between 1920 and 1924, covering the famous German hyperinflation. This setup comes with a number of advantages. First, we can directly observe investment decision making under inflation, something prior literature has not done. Second, inflation rates during our sample period were very high, ensuring that investors paid attention to inflation. Finally, we have monthly inflation rates for all towns in Germany with more than 10,000 inhabitants, allowing us to compare the investment behavior of clients being exposed to different inflation rates in the same point in time.

Despite these advantages, some of you may wonder how representative a sample of individual investors from 1920s Germany is. In a number of comparisons, we find that our clients are representative of the individual investors of the time and hold portfolios with similar characteristics as individual investors do today.

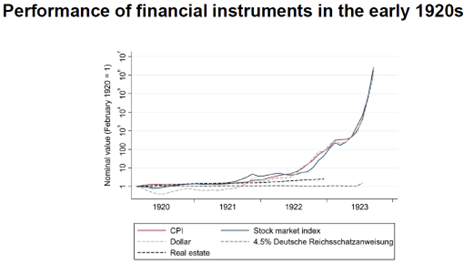

The following chart gives you a good idea of the performance of the potential financial instruments investors could use to hedge wealth against inflation during the early 1920s:

The figure shows that prices of stocks and the Dollar follow the CPI index, suggesting that both financial investments offered the ability to hedge wealth against inflation. However, owning and buying Dollars was subject to strict regulation, if not to say impossible. This leaves stocks as the only viable hedge against inflation.

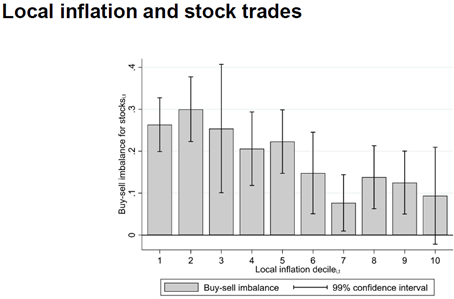

This figure visualizes our main finding. Each month, we sort towns in Germany into ten buckets based on their local inflation. Bucket one contains clients living in towns with the lowest monthly inflation and bucket ten contains clients living in towns with the highest monthly inflation. We then compute the average buy-sell imbalance of all investors in each bucket. The hedging hypothesis predicts that investors buy more stocks with higher inflation, an increase from left to right, while the money illusion hypothesis predicts the opposite. As the figure shows, we find a downward slope, which we take as evidence that individual investors’ behavior is inconsistent with the hedging hypothesis but consistent with the money illusion hypothesis:

In a large set of tests, we confirm that our results are not due to alternative explanations. For instance, we test whether investors sell stocks to finance consumption, whether investors sell stocks because local inflation reveals information about gloomy economic prospects of firms, whether local inflation increases investors’ risk aversion, and whether investors sell because they invest in assets that offer a better hedge against inflation.

To conclude, we find that individual investors buy less and sell more stocks when faced with inflation, which is consistent with money illusion and inconsistent with hedging. The open question is: how relevant is the finding that investors sold stocks under higher inflation one hundred years ago? We are cautious in drawing strong conclusions for today’s time period, but we are concerned that individuals do not understand that stocks offer the ability to hedge against inflation. Hence, financial education programs and financial advice should aim at improving financial literacy of investors, in particular, on how to protect wealth against inflation.”

Inquire Europe members can access the research and the presentation slides via: https://www.inquire-europe.org/event/joint-spring-seminar-2023/.