The value vs growth debate turned a new corner in 2021 when value started outperforming after a dismal period. What has exactly been impacting the factor in the past three years? Raul Leote de Carvalho (BNP Paribas Asset Management) presented his research ‘Value versus Glamour Stocks: The Return of Irrational Exuberance?’ during the recent Inquire Europe autumn seminar. According to the research, the difference between valuations of the most expensive versus the cheapest stocks (i.e. the value spreads) may have started a new period of compression at the end of 2020, led by shrinking differences in earnings growth forecasts.

The following quotes have been extracted from Raul Leote de Carvalho’s presentation during the seminar:

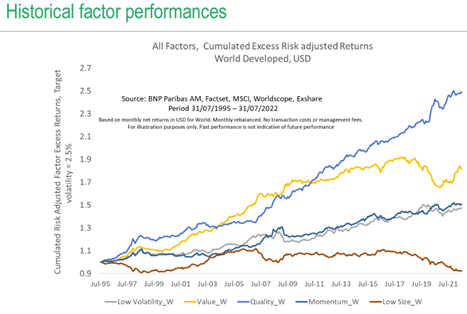

“As we entered the pandemic, equity quant managers were already suffering from poor performance, and actually throughout the pandemic it was quite disappointing. Along with Momentum, Quality, and Low Risk, Value is a dominant factor that quant equity strategies have exposure to. The value factor is about finding the companies that are the cheapest and buying them, you sell those that are the most expensive and expect the cheapest to get the highest returns, which becomes your source of excess returns.

But this didn’t work in 2019 nor in 2020. What was puzzling was that the cheapest companies kept getting cheaper. And those that were the most expensive just kept getting more expensive. Prices just kept moving away from fundamentals and the value spread kept widening. This is why the Value factor performed so poorly. Even if Momentum, Quality and Low Risk did well, quant managers still had bad performances because of Value, and the more Value they had the worst they performed. And those who relied on the Size factor did even worse.

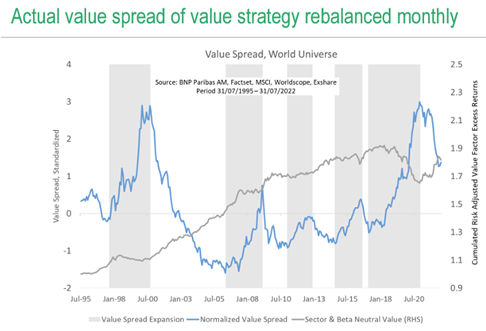

The value spread finally peaked at the end of 2020, interestingly at levels only seen at the peak of the tech bubble in 2000. Throughout 2021 and 2022 we saw normalization and prices seem to be converging towards fundamentals again. We now expect that value strategies will do better than average, much like they did from 2000 through 2006 while the tech bubble deflated.

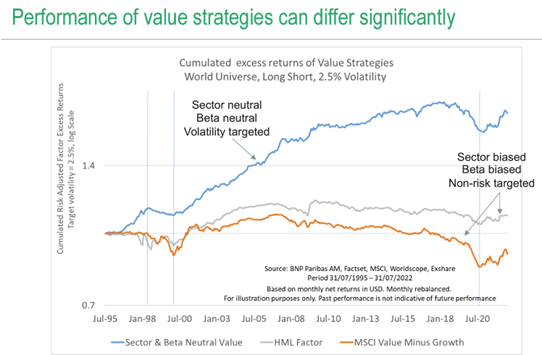

However, there is really no agreement on how managers should be picking the cheapest stocks and selling the most expensive. Quant managers tend to do it in a specific way, which is not exactly the same as academics and not the same as fundamental equity managers. And the truth is that the value definitions of academics and fundamental managers did significantly worse than those of quant managers, underperforming since 2009. When we talk about value, we sometimes get the sense that no one is really is talking about the same thing. That creates a lot of confusion.

Of these three key definitions of value, the first, preferred by fundamental equity managers, uses the MSCI Value index as a proxy and looks at the difference between its returns and those of the MSCI Growth index. The second is a proxy for the academic definition of value, and is something similar to the ‘High minus Low Fama-French factor’. For the third, a proxy for what quant equity managers use, we have a diversified set of indicators of value, but unlike the MSCI indices we control for sector bias, beta and tracking error risk.

The MSCI definition of value really sees value as the opposite of growth; but it is defined by not only taking value indicators but also growth indicators. Value stocks are the cheapest stocks with the lowest possible growth and growth stocks are the most expensive stocks with the highest possible growth. If you do not control for sector then you know that your portfolios of value stocks and growth stocks will have strong sector biases because stocks in certain sectors (e.g. tech) simply have higher valuations and higher growth than stocks in other sectors (e.g. utilities). The sectors biases end up playing a huge role in what fundamental managers consider to be Value stocks.

Quant managers, however, control for sectors. They do this because sector returns are driven to a differing degree by macroeconomic factors and much less by differences in relative valuations. And that does not help if all you want to do is capture a premium from converging valuations of cheap versus expensive stocks.

The performance of value strategies differ significantly. We can attribute those differences mostly to sector biases. In the last 20 years, if you controlled for sectors, like quant managers tend to do, you would have successfully captured a value premium despite the bumpy ride in the run up to the tech bubble and now in 2019 and 2020. If you tried to capture a value premium without controlling for sectors then you are probably deeply disappointed with the underperformance since 2009.

To understand why, it helps to know where the value premium is coming from. Let’s think about the mechanics. We can show that the value premium (i.e. the difference between the returns of the cheapest and the most expensive stocks) consists of three things: the difference between their dividends, the difference between their growth of fundamentals and the changes in value spreads. If you control for sectors you are essentially reducing the importance of the first two terms because dividends and growth of fundamentals are much closer for stocks from the same sector.

You are then left with the changes in the value spread explaining most of the value premium. If you buy cheap stocks and sell expensive stocks from the same sector and wait for the value spread to tighten then you get a positive value premium. . Therefore sector neutralization should help us to be sure that we are truly capturing a value premium from the convergence of prices to fundamentals. You will need to buy the biggest valuation gaps and during the period that you hold those stocks, the value spreads should shrink.

But reality is a bit more like this.

Prices are not always converging to fundamentals even if you control for sectors and Value spreads are not always tightening. We have periods where they have diverged.

Quant funds have been doing well in 2021 and this year, especially those that were using the Value strategy. And the reason is that the Value spreads have been tightening. They haven’t really fully corrected yet. If we were to see a repetition of the episode we saw after the 2000 tech bubble, there’s really a long way to go.

The lesson is that for Value factors built like this, even controlling for sectors will not prevent future episodes of under-performance driven by expanding value spreads, which should arise every time differences in earning growth forecasts increase.”

Inquire members can download the full paper here.