In the past decade, green bonds have gone mainstream. According to statistics derived from the Climate Bonds Initiative, investors have cumulatively loaned $2.3 trillion in the form of green bonds, meaning that they have become an important financing instrument to combat climate change. However, the EU only recently agreed to the European Green Bonds Standard, using its own taxonomy to determine what constitutes a sustainable investment across different sectors.

Additionally, there are significant knowledge gaps which must be filled to help various stakeholders understand how green bond issuance impacts firms as well other bond holders and bond pricing.

During the Inquire Europe spring seminar Hui Xu and Emanuela Benincasa presented their respective research ‘Actions Speak Louder Than Words: The Valuation of Green Commitment in the Corporate Bond Market’ and ‘Different Shades of Green: Using Natural Language Processing to Estimate Green Bond Premium’, both of which address interesting developments in the green bond space.

For those who were unable to attend their presentations, a summary has been made, beginning with Hui Xu:

“Green bonds are very important financial instruments employed to fight climate change. The definition of green bonds is simple: as long as the proceeds from bond issuance are earmarked for green projects or green assets, they are eligible to be labeled as green bonds.

According to our analysis, almost 90% of green bonds are senior unsecured debt, suggesting that most of the green bonds share the same seniority with other conventional bonds. One immediate implication we can surmise is that the benefits of green bonds and their assets should also accrue to other existing bondholders. Once a green bond is issued and when the assets are in place, the other existing creditors also have a claim on the green assets, as the green bonds do not have exclusive ownership. In other words, other outstanding bonds also become quasi green bonds.

However, the traditional view stipulates that new bond issue is usually detrimental to bond holders because it will increase the leverage and therefore the credit risk, and it will dilute the creditor’s claim on the assets. Consequently, a tension rises between green bonds and outstanding conventional bonds.

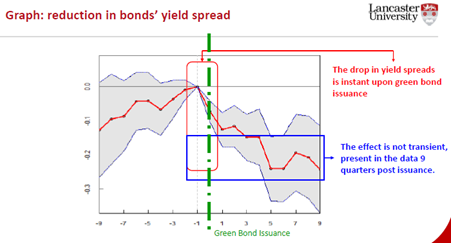

It is precisely this conflict of interest between the green bond investors and other existing creditors that motivates our research. What is the impact of green bond issuance on outstanding bonds from the same issuers? We have concluded that it in fact benefits existing bondholders. We find a reduction of conventional bonds’ yield spreads by 8 basis points when green bonds are issued by the same issuer. Additionally, we show with our analysis that the green market benefit is more pronounced amongst those issuers who have had weaker ESG performance in the past.

Please see the graph for a clear illustration of this:

Our paper also contributes to the understanding how the pricing effect is driven by increased demand from socially responsible investors. The analysis suggests that the positive effect of green bonds doesn’t depend on the existence of a ‘greenium’, i.e., the yield difference between green bonds and conventional bonds. It does provide a wider capital benefit to the firm who is issuing the green bond, thereby lowering the firm-wise cost of public debt capital.

Emanuela Benincasa:

“It is clear that a shift towards an environmentally sustainable economy must be made in order to address climate change. The increase in green bond issuance to raise capital for green investments is clearly linked to this need.

Many people wonder if there exists a ‘greenium’ for investing in green bonds. Empirical evidence argues both in favor and against the existence of a ‘greenium’. Moreover, additional questions arise, such as why firms issue green bonds in the first place? To begin, investors are willing to pay a premium for greener firms. However, theory predicts that there are conflicting motives including signaling, greenwashing and the cost of capital motives. Of those motives evidence suggests that signaling may be most dominant.

At this point there is little known about the implications of a green bond’s use of proceeds for the bond pricing, which led us to formulate our research question: does the disclosure and the difference in the content of green bonds’ use of proceeds have implications for bond pricing?

And, yes, we do find evidence that green bonds trade at a premium that varies with the greenness of the bonds’ use of proceeds. This suggest that green bonds are a cheaper source of debt financing, which is in favor to the cost of capital motives.

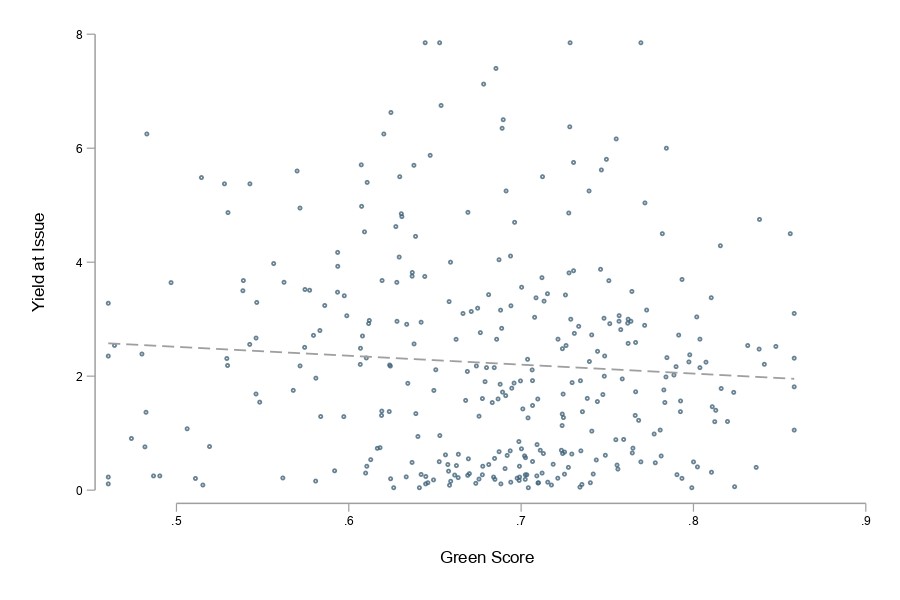

We exploit Natural Language Processing techniques to assess the content and information disclosed in the use of a bonds’ proceeds of green bonds. In doing so, we create a novel text-based measure, the Green score, to assess the similarity and alignment of the use of proceeds to the Green Bond Principles voluntary standards.

Figure 1 plots the Green score –our measure of the greenness of the use of proceeds- against bonds’ yield at issue, showing a negative relationship between the two.

Figure 1: Correlation between Yield at Issue and the Green Score

Our key findings show that the ‘greenium’ is driven by higher interest saving and lower riskiness for greener bonds. This indicates that investors are willing to accept lower interest payments and the greener bonds are perceived as being ‘less risky’ in the market.

Additionally, issuing greener bonds has a positive spillover effect on the pricing of a subsequent non-green bond issuance. However, we find that the effect is transitory and exists only within a 30-day period.

To conclude, in our paper we attempt to contribute to the green bond literature, questioning whether the heterogeneity in the information about the use of proceeds can tell us something about the greenness of green bonds, and whether this is a determinant for the pricing of these types of debt instruments.

By creating a novel text-based measure, we examine the similarity in content between use of proceeds and the green bond principle standards and find that green bonds actually do enjoy a ‘greenium’ which varies with the greenness of the use of the proceeds.

Our findings may be particularly useful as a voluntary guide for market participants in the investment decisions, particularly when subscribing to the EU Taxonomy green classification system.”

To access their presentations and research in full, please visit: https://www.inquire-europe.org/event/joint-spring-seminar-2023/