For those who were unable to attend, we compiled the key takeaways of the webinar featuring Professor Pierre Collin-Dufresne from the Swiss Finance Institute of the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne.

Collin-Dufresne’s research focuses on constructing a theoretical model portfolio where volatility and transaction costs are time-variant. The professor pointed out that many of the dynamic portfolio models presented in the academic literature are difficult to implement in practice, as they miss realistic frictions such as transaction costs, price impact, size, and liquidity constraints. To solve that issue, he developed a framework that can derive analytical results on optimal portfolio choice in a setting where there can be many predictors for returns. In doing so, the framework enables optimal asset allocation for specific liquidity regimes, such as one where both volatility and price impact are high, for example.

His work builds on prior research on a tractable portfolio choice framework, which Collin-Dufresne refers to as the Linear-Quadratic (LQ) framework. “However, using this framework comes at a cost”, Collin-Dufresne explained. “This framework requires a selection of simplified assumptions. For example, it must assume that covariance matrices are constant, and it also assumes that price impact is constant. What we essentially do in this paper is relax those assumptions.”

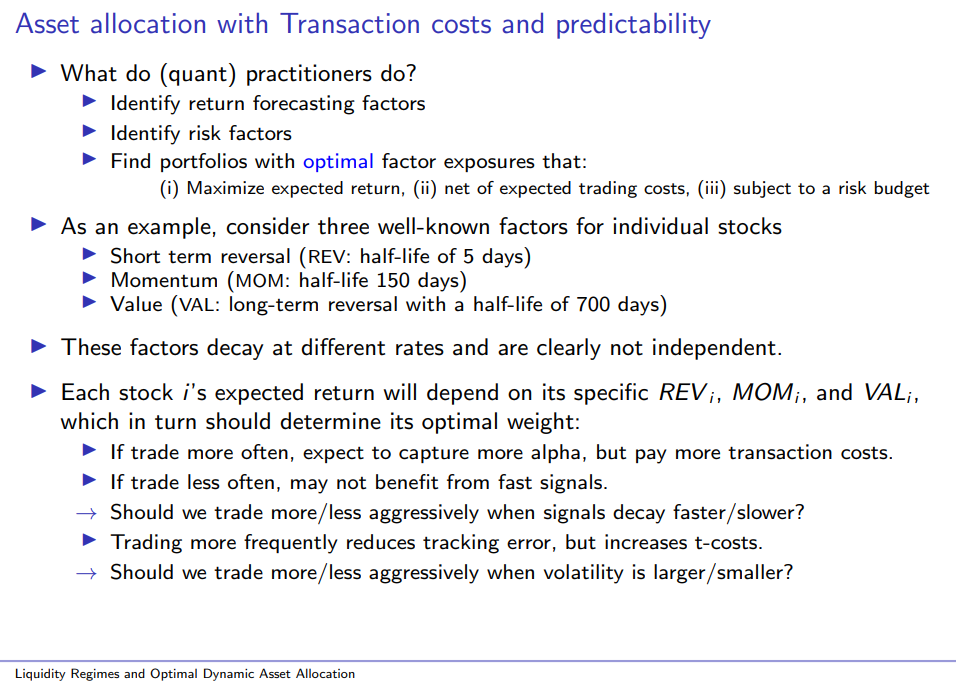

Before elaborating on his own framework, Collin-Dufresne discussed the insights he gathered from studying the LQ framework. Amongst other perspectives, he touched upon the importance of transaction costs on asset allocation: “Different factors for individual stocks decay at different rates and are clearly not independent,” he explained. “Without transaction costs, we can simply go in and out of positions without any costs. However, once we trade a portfolio where transaction costs matter, you can immediately see that it is going to matter greatly whether we have expected returns coming from fast decaying signals or whether they are coming from slow decaying signals. That is what we are trying to understand – how should we allocate and rebalance across portfolios? Should we trade more often, because otherwise we risk losing out on that source of income for fast decaying assets, or should we trade slower because we might pay too many transaction costs to get there?”

Subsequently, the professor went on to introduce his Liquidity Regime Switching Model and explained how it could be applied to different liquidity regimes – using the example of a ‘high’ state (an environment with high volatility and high transaction costs) and a ‘low’ state (an environment with low volatility and low transaction costs). “Our paper essentially formulates the problem similarly to the LQ model, but the new twist is that we allow volatilities and price impact matrices to change. By using regime shifts, we assume that there are discrete regimes and as we move from one regime to the other, expected returns, covariance matrices and price impact matrices are changing.”

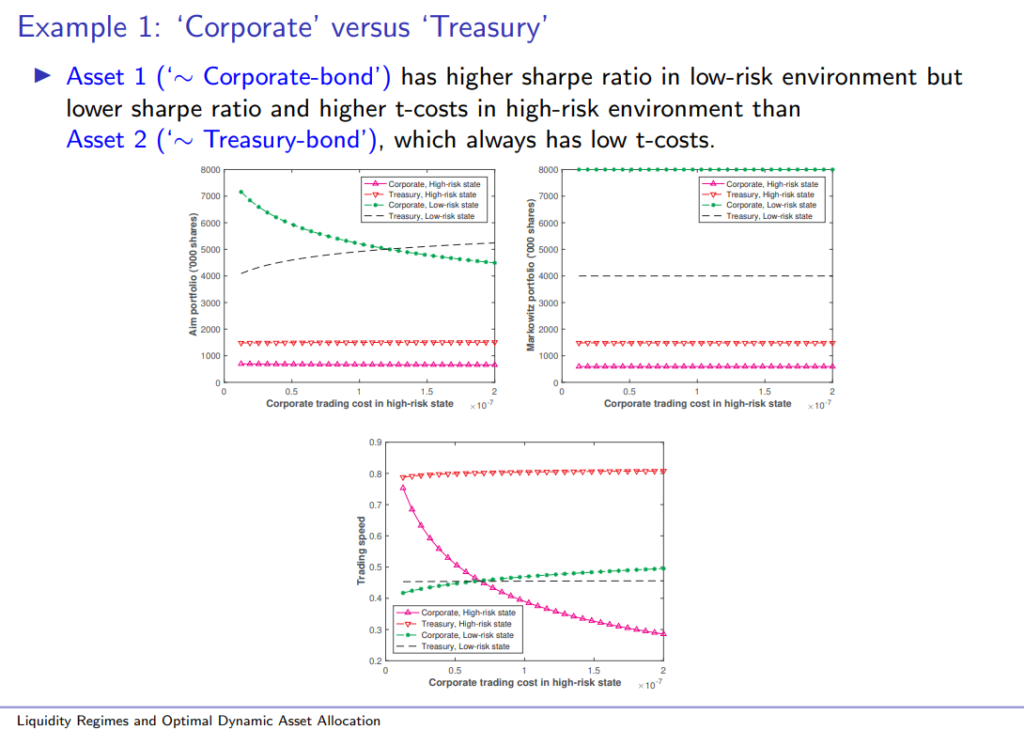

Before concluding the presentation, Collin-Dufresne provided an example of how his framework could compare allocation to corporate bonds and treasury bonds in the two aforementioned states. “In the low-risk regime you would be heavily invested in corporate bonds. The corporate bond has the highest Sharpe ratio and since there are no transaction costs, I would go all the way: I would buy a lot of corporate bonds and I would also be highly invested in treasuries. However, when I suddenly shift to a high volatility regime, I need to deleverage, because suddenly the Sharpe ratios on both assets drop. As the corporate bond’s Sharpe ratio drops sharply, that’s the one I deleverage most.”

“As I increase the costs of trading, what changes the most are my assets in the ‘high’ state”, Collin-Dufresne continued. “You see that the high-risk asset, the corporate bond, will dramatically start to drop. Since I anticipate that I might switch to a crisis state where the corporate bond’s Sharpe ratio will drop dramatically and the trading costs will increase, I drop my exposure to the corporate bond – to an extent where you might hold an optimal position if you actually hold less of the dominant asset.”

Interested in learning more about the research?

Read the paper or watch a replay of the webinar here: