For those who were unable to attend, we compiled the key takeaways of the presentation given by Hens Steehouwer, Head of Research at Ortec Finance.

“What do we do when things start to get complex? We start building models,” exclaimed Steehouwer. “Models are simplifications of reality, that can be used to experiment and gain insight on which type of scenarios would work well to achieve our objectives.”

By using models, it is possible to perform analysis to support investors in making the right decisions for the future.

“Every time there is a crisis, as there was in 2008, and as there is now, I have noticed that there are a lot of questions being asked about the models themselves. People wonder why practitioners still use them, assuming that they are obsolete because the world is completely different now.”

Steehouwer explains that it is important to consider that the classification of the models used in economics and finance is very different from those that are used in natural sciences. “The models we use are based on assumptions, meaning that the accuracy witnessed using models for space exploration, for example, can simply never be achieved.”

Steehouwer reiterates that it is therefore essential to use models in a sensible way. “Sometimes in the heat of the moment, we forget that we need to validate assumptions, include parameter uncertainty, avoid sampling noise, and perform sensitivity analysis. It is also essential to remember that we need to make realistic assumptions. That said, remaining realistic does not equate to being prudent, consensus thinking, using intuition or rationality or even enjoying simplicity.”

Scenario approach

Using what is known as a scenario approach has proven to be very successful for investors in decision making. “It is important to emphasize that in reality, everything happens at the same time: Covid-19, climate change, elections. These all lead to certain interactions and dependencies between asset classes, regions, economies and sectors. This means models must be designed in a multi variate setting.” Steehouwer explains that this approach is most constructive because it is so flexible. There are few limitations to what you can simulate with these models, which is important because it allows practitioners to design them to reflect the most realistic scenario. Additionally, despite the fact that they tend to include a lot of tedious calculations, they yield results that are easily communicated to decision makers.

According to Steehouwer, it is key to make the transition from analysis to easily translatable insights for clients using risk-return frameworks. By continually searching for more efficient and effective strategies, it is possible to steer the decision-makers on the right path.

In practice, constructing scenarios can be as simple as taking historical averages or can be done using historical simulation. It can also be done using a bespoke method of creating scenarios by formulating what might happen in the future based on specific narratives of possible events. “I see this used increasingly as the world gets more complex. It relatively simple, it stimulates out of the box thinking. But the limitations are that it cannot capture all uncertainties, making it difficult to take the step towards assessing the risk-return trade-offs.”

The model-based approach is most relevant for quantitative practitioners. It which follows a process of 1) assume 2) model 3) calibrate 4) generate and validate. “The objective is not to be a forecasting machine – that isn’t possible, we don’t have a crystal ball. But we can make an assessment of what the range is of potential outcomes. In this way, we can back test our models thereby gaining a realistic representation of what is happening in the world.”

Horizon and frequencies

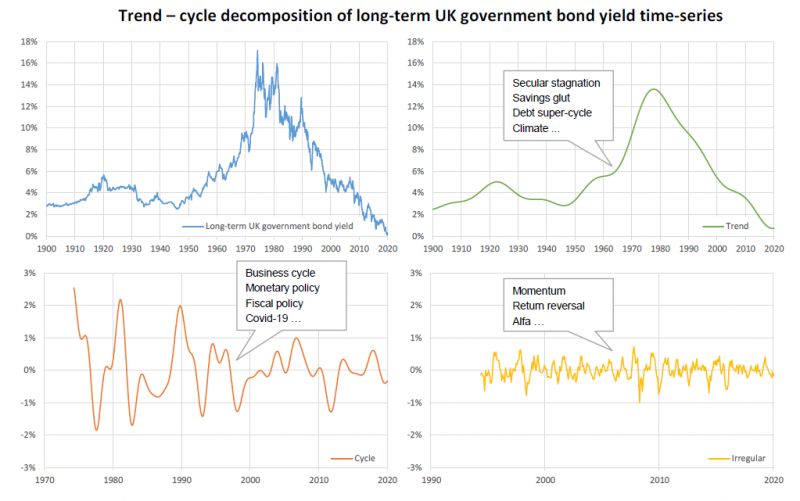

How long ahead are you projecting your scenarios and how frequently should the data be assessed? Steehouwer suggests using trend-cycle decompositions illustrated with an example on long-term UK government bond yields.

“This is useful because typically many economic or financial market phenomena can be attributed to a specific component. Meaning that when forming assumptions, you can do it in a piecewise manner. And that enhances the overall realism of your model.” It can also help to synthesize long, medium and short term modelling because it helps to approximate the terms for different holding periods.

Steehouwer believes frequency domains could be beneficial to use more often because it captures the manner in which economies and financial markets are constantly fluctuating. It calibrates the type of movements that are made and if they correlated. “It is a very natural way to analyze these dynamics in the markets.”

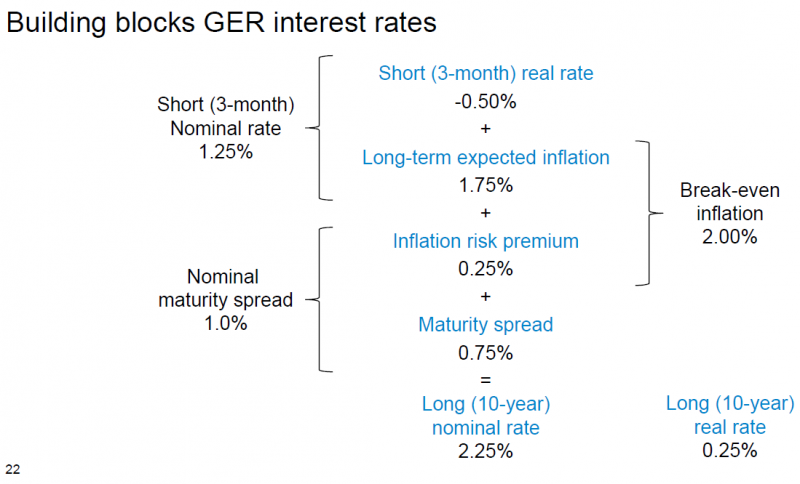

When considering long term horizons in a scenario modelling framework, Steehouwer suggests using a building block approach, as seen below in the example on estimating German interest rates.

Climate scientists utilise scenario analysis to predict the outcomes of climate change. Steehouwer points out that a big difference in their modeling is the horizon, which is often 100 years. “The decisions we make now will determine what will happen in the long term. The objective in the case is to combine financial and climate modeling and monitor the interaction. Currently climate informed investment decision making is being done predominantly from a top-down perspective in scenario analysis, meaning the goal is to gain a holistic view of climate risk and calculate it macroeconomic implications to asset with strategic asset allocation an asset liability management.

View the webinar in full via: https://click.email.vimeo.com/u/?qs=af34224b7f1fb50f0a40560399c47b6a4c2c04788d18bcc7526dc719a6a88898c793e3d5af7b70ec4c648b1391e44a22cef9dab9a6ce34f4bfbfa08cdd7ed0e0

Download Hens Steehouwer’s presentation here.