Due to an increasing amount of assets under management in passive strategies, the importance of indices has risen substantially in recent years. The asset demand created for benchmark securities has substantial pricing implications for underlying constituents. Ultimately, these pricing effects also have real implications for corporate investment policies.

These developments give rise to a number of relevant questions. To what extent do funds select stocks from the universe of benchmark securities? How do passive and active investment funds respond to changes in an underlying benchmark? And how do stock characteristics moderate this response? Lennart Dekker, Jasmin Gider and Frank de Jong (Tilburg University) set out to answer these questions with their research, ‘How do Funds Deviate from Benchmarks? Evidence from MSCI’s Inclusion of Chinese A-Shares’.

Lennart Dekker presented on the findings during the Inquire Europe Autumn Seminar in October; a synopsis has been made for those unable to attend:

“A-shares are by far the largest subset of Chinese equities both in terms of the number of stocks as well as in terms of market capitalization. Chinese A-shares therefore presented a huge opportunity set for investors. By including these A-shares, the MSCI EM index would better reflect the global economic weight of China, which was the main motivation for MSCI to start including A-shares. In total, the entire inclusion of the A-shares led to a weight increase of China in the MSCI Emerging Market index by approximately 5 percentage points, which is substantial.

This event gives rise to some interesting research questions. First, we set out to understand how investors responded to the inclusion of Chinese A-shares. In doing so, we focus on investment funds that are benchmarked against the MSCI Emerging Markets index and we distinguish between active and passive funds. We also examine how changes in ownership are related to stock characteristics. Secondly, we study the impact of index inclusion on the underlying A-shares, where we specifically focus on return co-movement.

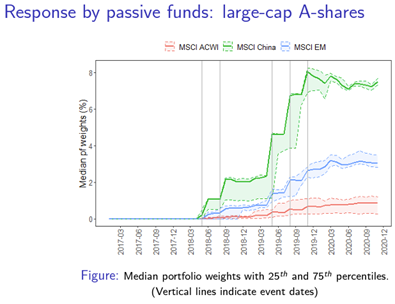

First, we look at how passive funds responded to the inclusion of Chines A-shares in the MSCI EM index. The figure shows the median portfolio weights of the passive funds in our sample that are allocated to the large cap A-shares that were initially included in May 2018. The jumps in portfolio weights align nicely with the actual event dates at which the index weights of these A-shares increased, so passive funds responded closely to the timing of the index changes.

We next address the question whether funds bought all the included A-shares or just a subset. Can we detect if there are characteristics which would have encouraged investors to buy certain stocks We believe that there is a trade-off that passive investors face. On the one hand they must stay close to the index to minimize tracking errors, but on the other hand they must keep their transaction costs low. As a result, it may be optimal to invest in a subset of the benchmark securities, which is called sampling. It may for instance be optimal to omit the least liquid stocks from a passive portfolio, which saves on transaction costs and only leads to a modest increase in tracking error.

With that trade-off in mind, we zoom in on December 2019, when 481 A-shares were eligible for the index. We find that funds deviated substantially from the index by not buying all the included A-shares, and we also observe a lot of heterogeneity across funds.

What characterizes the subset of A-shares that funds did actually buy? Passive funds tend to favor larger and more liquid stocks as opposed to smaller and less liquid stocks. This is consistent with the trade-off mentioned before: keeping transaction costs low while at the same time minimizing tracking error.

We then focus on return co-movement, and whether it increased after the A-shares were included in the index. Once a stock is included in the index it is also bought by index-tracking funds and hence flows from and to these funds would translate into correlated trading of the underlying securities. That would be the mechanism through which index changes would lead to higher return co-movement via passive investors.

The stock characteristics we consider are again related to size and liquidity because we want to test if the same characteristics that are related to sampling also moderate the impact of changes in index weights on return co-movement. We indeed find some evidence that larger and more liquid stocks faced higher increases in return co-movement than smaller and less liquid stocks.

Finally, we zoom in on a specific subset of A-shares with a dual-listed H-share. H-shares form an excellent control group because they reflect identical fundamentals. In total, we identified 80 pairs of dual-listed stocks. Before inclusion, H-shares show substantially larger co-movement with index returns than A-shares. This gap narrowed down after increases in the A-shares’ index weights.

To conclude, we find that actual investor holdings deviate from index weights, implying heterogeneous effects of benchmark changes. This deviation is driven by stock characteristics related to the trade-off between minimizing tracking error and minimizing replication costs. The same characteristics seem to explain some variation in changes in return co-movement, although estimation remains challenging.”

Access the complete research via the Inquire Europe archive.