The digital representation of a broadening array of rights and assets has enabled a new scale of market efficiencies and possibly also democratized access to previously unavailable investment asset classes.

Tokenized investing in real asset markets is becoming increasingly prominent, and it is therefore necessary to better understand the potential and limitations of this radically new development in financial markets.

Laurens Swinkels presented on his recently published research ‘Empirical evidence on the ownership and liquidity of real estate tokens’ during Inquire Europe’s autumn seminar in October 2022.

For those of you who were unable to attend, we have created a synopsis:

“There are several existing studies on the theoretical possibilities of tokenization, but very little has been researched on what happens in the real-world practice of tokenization. I was interested in multiple questions: after being tokenized, how many owners does the average residential property have? Do token investors use their fractional ownership to create diversified real estate portfolios? How liquid are individual residential properties after tokenization? Are prices of tokenized assets related to economic fundamentals of the investment?

Let’s begin by gaining a basic understanding of how the tokenization of property takes place, in a practical way. Essentially, a group of investors purchases a house and thereafter puts it on an ‘initial token offering’ to the public; for example, investors issued 1100 tokens for a house which is worth $55,000 – making each token worth $50 – in the Detroit area of the United States. The family who is living in the house pays the rent and the token holder is – similar to a shareholder – subject to receive the dividends; in this case, it would be a return of approximately 11 percent.

The data that I collected was derived from a company operating in the Detroit area with residential properties, rendering 58 tokenized houses in the sample. Multiple new properties are tokenized and curated every week, and new investors can subscribe to the initial token offerings. Trading is typically done via Ethereum on the Uniswap and Swapcat platforms, and there is an app available to monitor how tokens are trading in real time.

Regarding the number of owners a property typically has, it was concluded that the dispersion of ownership was wide: between 15 and 700 plus owners. The average was 258 owners per property, indicating that there is real fragmentation occurring – which surprised me. A Herfindahl Index is also used to calculate the ownership concentration per property, which shows that there is also great dispersion here.

I then conducted research to understand if token investors use their ownership to diversify their real estate portfolios. My initial results showed that portfolios were largely undiversified, with many investors holding only one property. I then examined how much capital was invested per token wallet, which showed that those investors who were investing greater amounts of capital – more than USD 5,000 – were well diversified.

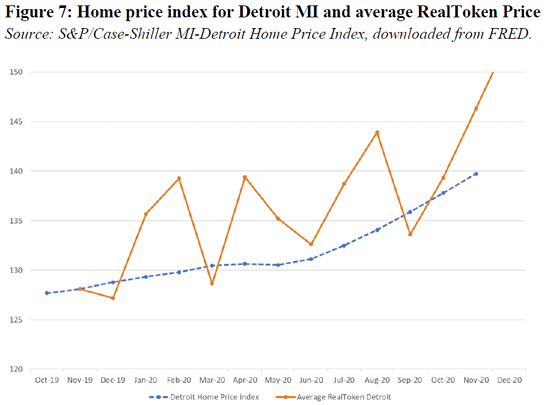

Real estate is not known to be a liquid asset. But tokenization could certainly impact that. Statistics gathered on turnover rates show that trading costs on Ethereum have a huge influence. On average, there was 100 percent turnover ratio, meaning that each house was traded once per year, but trading activity depends a lot on transaction costs and dried up nearly completely towards the end of my sample. This led the exchange to switch to a different blockchain. My sample does not include trading data of this new blockchain, so I cannot say whether turnover picked up again after trading costs were reduced again. Finally, I was also interested in the fundamental value of the properties which were tokenized. I looked at the Case-Shiller home price index for the Detroit area and as well as the price and I created an index. However, this is not a long sample cycle, so I’m not completely confident in my results – you see that it is quite volatile (see graphic below).

The graphic illustrates how these houses fluctuate in price; an econometric reading of it would report that it is in relative alignment with the Case-Shiller home price index. But I would like to have more direct evidence about home prices in the Detroit area to draw a stronger conclusion.

My conclusions have revealed a bit more about the real estate token market – about which there was previously very little known. I am enthusiastic because what I have learned exceeded my expectations, and there is a lot of space to expand upon my initial findings.”

Access Mr. Swinkels’ presentation and research via: https://www.inquire-europe.org/event/autumn-seminar-2022-marseille/